英国滑冰传奇

Harold Wilkinson

Harold Alexander “Wilkie” Wilkinson was born in Malpas Road, Brockley, London on 31st October 1907 and the youngest of five children born to John and Susannah. John, originally from Canterbury, was a travelling butcher’s agent which meant that he would often move around the City plying his trade.

By 1911 the family were now living in Catford and although the area had its own roller rink and club at that time it would be another twelve years before Wilkinson would don a pair of roller skates. Aged eight, tragedy would strike the Wilkinson household when Harold’s older brother, Percy, was killed in France in 1915 fighting in the First World War.

Wilkinson’s first venture onto eight wheels came at the age of fifteen at the County Rink in Ramsgate in 1923. A year later and he entered his first race, although his initial interest lay with hockey and he started playing for Ramsgate Argyle junior team in 1925. His first medal was silver in the Gladden Cup at Herne Bay in 1927, but his speed skating exploits were secondary to his hockey at that time. By 1928, however, he had moved back to London and initially played roller hockey for Kingston before joining the Brixton ‘All Blacks’ speed skating team. Here he found himself training with the likes of current One Mile Champion, Charlie Bush and Len Stewart (who would go on to represent Great Britain in the Olympics at ice skating). Like many skaters at that time Wilkinson would continue to mix his new found passion for speed skating with the continual playing of roller hockey. He was quite adept at both and the acceleration he required to play hockey would pay dividends throughout his speed skating career.

Whilst Wilkinson’s initial efforts at speed skating were seen as somewhat sporadic, in February 1929 he entered the Five Mile Championship at the Cricklewood rink. The three heats were run over two consecutive days, 5th and 6th February, with the final being run on Thursday 7th February. Wilkinson was placed in heat two and crossed the line in third place. His time as the fastest third placed skater meant that he qualified for the final. The race was eventually won by Jimmy Reed (Alexandra Palace) and whilst Wilkinson did not place in the final, he put up a good effort which got him noticed amongst his fellow finalists. A few weeks later he entered the inaugural running of the half mile handicap Seagrave Cup at the Alexandra Palace, coming home in second place to local skater Arthur Reece. On 25th April Wilkinson would win his first gold medal. The race was a mile handicap for the Lee Cup, again at Alexandra Palace. Wilkinson was now up and running and getting swifter by the day.

For a few years the Brixton All Blacks had organised a road race from London to Brighton (52 miles) that was usually held around September/October time. In 1929 the event took place on 6th October. As with every year the skaters, of which Wilkinson was one, started out on the road where Westminster Underground Station faces the Houses of Parliament and as Big Ben struck 5am the men’s group started their journey (the women having set off at 4am). Before the group reached Croydon the heavens opened and torrential rain of almost tropical intensity soaked everyone and a boisterous head wind made the going extra tough. Near Coulsdon the road was several inches deep with rainwater and the skaters had to virtually wade their way through. Len Stewart, the 1928 winner, broke an axle near Streatham and he fell back several miles leaving Wilkinson now out in front. Wilkinson would eventually come home first in a time of 4 hours and 55 minutes with Stewart a plucky second.

Shortly after Wilkinson’s victory the Brixton rink decided that they no longer wanted to house the speed skating and roller hockey club at their facility. The result was that from now on the club would effectively become nomads as they trained and raced at the various other rinks in and around London.

On 13th March 1930 Wilkinson secured his first British Championship medal. The event was the Five Mile Championship at Alexandra Palace and Wilkinson would take home the bronze. Ahead of him were Jimmy Reed (Alexandra Palace) and Bill Ross (Alexandra Palace), both considered to be elite skaters of their time. A week later and Wilkinson would take gold in the National Skating Association (NSA) one mile handicap at Alexandra Palace ahead of a fast finishing Bill Ross.

Unlike some skaters of the time Wilkinson was not afraid to take his skating further afield if it meant he could race. His hockey playing also helped in so far as the sport was more widely spread across the country. His regular visits to other rinks meant he could familiarise himself with their individual sizes and floors and he would often race around them to get a feel for their individuality. On 24th May 1930 he would win his first scratch race, the one mile race for the Jesson Cup at the Boulevard rink in Leicester. On 29th November (the 1930/31 season) he again travelled to Leicester and repeated the feat, thus retaining the famous Jesson Cup.

In September Wilkinson attempted to also retain his London to Brighton title. He had led for several miles when going down Handcross Hill he fell badly. Despite regaining his feet he then struggled with cramp which eventually resulted in his retirement from the event.

On 15th January 1931 Wilkinson reached new heights. The One Mile Championship for the Benetfink Cup was held on the Alexandra Palace rink and despite the likes of favourites Jimmy Reed, Bill Ross and Eddie Stumbke all taking part it was Wilkinson who would cross the line first to win his first British title. Not only that but he did it in a new track record time of 3 minutes and 19 seconds.

A return to Alexandra Palace on 29th January for the British Relay Championship saw Wilkinson help his team to the final against the much fancied Alexandra Palace club. Despite a great effort it was the Palace team that was victorious whilst the All Blacks (having now dropped ‘Brixton’ from their name) had to settle for second place. In February the Half Mile and Five Mile Championships resulted in a further two bronze medals for Wilkinson and he was now seen as a skater more than capable of winning.

1931 was to be an even more eventful year for Wilkinson when towards the end of the year he would marry his fiancé, Winifred Cox. On 19th November he entered the NSA open one mile handicap at the Alexandra Palace rink. Being the reigning One Mile Champion Wilkinson was made the scratch man and although he would eventually place second behind Daniel Howard (Alexandra Palace) who was given 75 yards, it was Wilkinson’s performance against Jimmy Reed that had everyone taking note. Reed was believed to be unbeatable in a sprint on his home track and given the fact that he had 5 yards head start on Wilkinson many thought it a foregone conclusion. However, Wilkinson first passed Eddie Stumbke (Alexandra Palace) and then on the final straight pipped Reed to the line in a head to head sprint. Some believe that the narrowness of the track prevented Wilkinson from passing Stumbke and Reed earlier and probably a victory, but even though he placed second, he was now very much seen as the ‘man of the moment’. On 12th December (1931/32 season) Wilkinson again retained the Jesson Cup. His three consecutive victories, the first time ever since it was inaugurated in 1909, resulted in Wilkinson being awarded the trophy outright by William Jesson himself. This meant that for the following season a new trophy had to be found which is the one that we see today now owned by the Federation of Inline Skating (FISS).

In May 1931 the Norbury rink reopened and for a short period the All Blacks team found themselves with a new home. Whilst the rink was too small for racing it did allow for training sessions and the playing of roller hockey.

Despite the euphoric ending to 1931, 1932 would be a comparatively lean period for Wilkinson. He still raced periodically, and despite finishing fourth in the One Mile Championship in February of that year his overall medal tally was confined to relay medals only. On paper one might think that Wilkinson had gone off the boil but the truth was that Winifred was pregnant and towards the end of that year the couple were blessed with a daughter. Despite juggling his job as a motor drive with his passion for roller skating, Wilkinson put his focus firmly on his family as they then moved to Streatham as he embraced fatherhood.

Wilkinson’s passion for roller hockey was also undiminished. In 1932 he travelled with his All Blacks roller hockey team to Switzerland and played in a series of international matches. He was also a keen spectator of ice hockey and was a regular visitor to the Streatham ice rink, now run by former roller skating legend Benny Lee, to watch his local team play their home matches. Wilkinson believed that much could be learned from ice hockey and he contemplated trying his hand at the sport but it never really came to fruition. Roller skating was really where his heart was at, for now at least.

The 1933 Half Mile Championship was held on January 26th at the Cricklewood rink. Despite having only just recovered from a bout of influenza Wilkinson achieved another bronze medal. A week later he was back on the rink in an attempt to regain his One Mile title, however, having led all the way in his heat Wilkinson unceremoniously fell just a couple of feet from the finish line which allowed Dan Howard (Alexandra Palace) to take a place in the next round. A month later and it was a silver medal in the Five Mile Championship at Alexandra Palace, won by the great Jimmy Reed.

By now the Norbury rink had once again closed its doors after a brief period of opening and the All Blacks again found themselves without a home. The club were allowed the use of the Cricklewood rink for training and the playing of hockey, but it was a difficult period as the rink now had its own hockey club, two speed clubs (Cricklewood and Broadway) and a roller dance club (Belmar) who always got priority. It made sense to Wilkinson to join one of the Cricklewood rink clubs and so made his mind up that Broadway was now to be the club for him (although he continued to play hockey for the All Blacks).

Almost immediately the stability of having a speed club with proper training facilities had a huge positive effect on Wilkinson. Not only that but the club consisted of some good speed skater like Les Savage, Eddie Cleaver and Eustace Cooper. On 31st January at Alexandra Palace Wilkinson would take his first British Championship medal as a Broadway skater when he placed third in the One Mile. Two weeks later, he would take his first Five Mile Championship gold, again at Alexandra Palace. Of the seven finalists Wilkinson was the only Broadway skater. With the pace was slow at the start he suddenly burst from the pack and headed for home with only Daniel Howard (Alexandra Palace) able to give proper chase and catch him. The pair battled it out for the last mile and as they crossed the line only inches separated them. They were both awarded exactly the same time but it was Wilkinson who got the nod and in so doing gave Broadway their very first British Championship title.

Another two weeks on and it was the British Relay Championships at Alexandra Palace. The final consisted of the local Palace team and Broadway. The race finished with Palace winning the title for a record sixth time and the setting of a new track record in the process, whilst Broadway had to settle for second.

If the successes of 1934 were to be applauded then 1935 would see Wilkinson be firmly recognised as the number one male skater in Great Britain. Within twelve months of joining Broadway he was declared the speed team captain. He was undoubtedly their best speedman and as 1935 unfolded he would cement that recognition even further. On 9th January he won his first Half Mile title on his home rink of Cricklewood with the Allworthy Cup being presented to him by NSA President, Viscount Doneraile. On 25th January he followed this up by retaining his Five Mile Championship title, this time at Alexandra Palace. As with the previous year it came down to a two horse race between Wilkinson and Howard. This is how the Skating Times [March 1935] reported the race:

“With about half mile to go Wilkinson sprinted to the front, Howard following closely. Three laps from the end Howard regained the lead and looked like being the victor but another splendid dash by Wilkinson took him ahead, and although Howard made a gallant effort in the final straight he was unable to pass Wilkinson, who finished comparatively fresh after a great performance. Howard threw himself over the finishing line and fell at the end”.

Once again mere inches separated the two skaters, and once again it was Wilkinson who took victory.

Wilkinson returned to the Alexandra Palace rink on 14th February to try and help Broadway to their first British Relay Championship. With the likes of Ross, Reed, Stumbke and Howard the Alexandra Palace club were once again clear favourites. In the early stages they romped ahead but as the race unfolded the gap began to close. Broadway had saved their efforts and on the last lap it was Wilkinson for Broadway pitched against his Palace rival, Jimmy Reed. Reed led as they entered the final straight but Wilkinson put in an almighty effort. They crossed the line virtually together with many of the spectators unable to determine who had won. Then the announcement came that Alexandra Palace were once again the winners and took home the Burgoyne Shield for a record breaking seventh time.

The final individual men’s British title of the 1934/35 season, the One Mile, took place at the Forest Gate rink on 13th March. Forest Gate had only ever been the venue for a men’s championship event once before, the Half Mile back in 1926. Wilkinson took the lead from the gun and set a hot pace. Behind him were the Palace skaters of Jimmy Reed and Daniel Howard who continually tried to pass the Broadway skater. Each time Wilkinson managed to out sprint them to the next bend and hold them at bay. The final sprint saw the three cross the finish line with only on tenth of a second separating first from third, but it was Wilkinson who would claim his third title of the year.

By winning all three titles, or the Triple Crown as it was more commonly known, he joined the ranks of Benny Lee (1924), Robert Symondson (1926) and Jimmy Reed (1929) as being one of only four skaters to have achieved that feat. Only Symondson had done so on three different rinks, and now Wilkinson joined him in that accolade. 1935 certainly belonged to Howard Wilkinson.

1936 also started off well for Wilkinson. A second place in the Southern Counties to local hero Pete Walters at Herne Bay was quickly followed up by his retention of the Benetfink Cup for the One Mile Championship at Granby Halls, Leicester, on 1st February. On 18th February on the Alexandra Palace rink Wilkinson finally achieved the one trophy missing from his collection, the Burgoyne Shield for the British Relay Championship. Broadway actually drew Alexandra Palace in the semi-final with the race between the two giant clubs declared by George Lord as “the greatest relay race for many years and one of the most exciting in the history of the championship”. By comparison the final, which consisted of Broadway and Aldwych, ran off without incident and as expected Broadway came home first winning their first ever British relay title. The race had originally been scheduled for 23rd January but the death of King Edward VII meant that it was postponed as a mark of respect.

As if this wasn’t enough Wilkinson also retained his Five Mile Championship for the second time at Alexandra Palace becoming the first ever skater to achieve the feat of three successive victories in the event. Unlike the two previous years, this year he won it comfortably having lapped the entire field by the halfway stage. Never in the history of the event had a skater done this in the final. Granted, Dan Howard did not enter due to an accident and Jimmy Reed had to retire in his heat with a broken skate, but Wilkinson’s status as the number one skater in the country was assured.

Around this time the Federation International de Patinage a Roulettes (FIPR), the world governing body for roller skating, announced that the first ever World Roller Hockey Championships would be held in Stuttgart, Germany, in April. Although the FIPR was formed in 1924 Britain were not members. Their roller hockey team, however, were unbeaten in European competition since the inauguration of the European Championships in 1911 and as a result, the FIPR invited the British hockey team to compete. An invitation was also extended to the British figure and dance roller skaters where the World Championships for that discipline would also take place. By contrast, speed skating was a late addition to the programme and then only as a European Championships. An international road event held in Antwerp, Belgium, in 1930 would eventually come to be recognised as the first ever European Championships with a follow up road event in Monza, Italy, in 1935. Great Britain did not take part in either of these events due to the fact that they were not affiliated to the FIPR and further, the NSA refused to recognise road racing as a legitimate form of racing. Until now the Association had only recognised track racing as ‘proper’ competitions. Despite their FIPR non-affiliation a specific invite to attend the track races of 1936 in Stuttgart meant that the NSA were only too willing to field a team.

As soon as the invite was given preparations for team selection got underway. George Lord laid out a track just nine feet wide at the Alexandra Palace to correspond with the three metre wide track in Stuttgart, a possible handicap for the British team who were used to racing on fifteen foot wide rinks. Trials began in earnest and surprisingly it was Bill Ross (Alexandra Palace) who showed much better staying power in the longer distances than his teammates Howard, Stumbke and Reed. Wilkinson did not take part in the early trials owing to an injury. Ross then also had to retire after straining a muscle. On the fifth night of trials Wilkinson took to the track and along with Stumbke, Howard and Reed was asked to cover seven miles as preparation for the 10000 metres event. The skaters were asked to do a lap each, which they did, but the pace was so high that eventually Stumbke and then Howard dropped back. It was now just Wilkinson and Reed who set the pace at the front. On completion of the distance they had set a remarkable pace of 3 minutes and 10 seconds for each mile. The team was shortly announced – Bill Ross would captain the team with Wilkinson and Reed being the other two skaters.

The team made their way to Germany where the European Championships would be held in the Stadthalle in Stuttgart between 1st and 5th April. Before a crowd of some ten thousand spectators the first day’s racing comprised of the early rounds and semi-finals of the 1000 metres and the mass start final of the 3000 metres. The 1000 metres was basically a knock-out competition contested between just two skaters in each round. Wilkinson progressed to the semi-finals which he duly won and set up a meeting with Raymond Mathis (France) to contest the final, scheduled for 5th April. Later that day the 3000 metres mass start was held. The British contingent led the race for most of the way but Mathis hit the front with three laps remaining and tussled with Wilkinson to the finish, eventually winning the event. That said, many believe that Wilkinson was odds on to win but the bell sounding the last lap was so faint that there was some confusion approaching the finish line whereby Wilkinson ‘stood up’ and Mathis charged past him for victory. Wilkinson would finish second and in so doing would win Britain’s first ever medal at a European Championships.

The following day saw the early rounds and semi-finals of the 500 metres. Whilst Wilkinson progressed to the semi-finals he would progress no further. The 5000 metres was then held in which Jimmy Reed would bring home Britain’s first ever European gold medal and behind him was his teammate Wilkinson with his second silver of the championships.

The third day saw the heats of the 1500 metres where heat winners would progress to the final, again to be held on the final day of racing on 5th April. Wilkinson again made sure of his place in the final meaning come April 5th he had both the 1000 metres and 1500 metres to contend, but before the day would end there was the small matter of the 2000 metres title to contend. A euphoric Wilkinson crossed the line first and so became the second British skater to win European gold.

Whilst the first three days had proved fruitful for Wilkinson having already bagged a gold and two silver medals, the fourth day proved disastrous for him. Having not qualified for the 500 metres final he could be a spectator and save himself for the 10000 metres mass start race. As a triple Five Mile British Champion it’s fair to say that Wilkinson was looked upon as one of the favourites to bring home gold. With only four laps completed, however, one of the competitors ahead of him fell bringing him, Jimmy Reed and a number of others down with them. Whilst the others regained their feet and gave chase Wilkinson hit his head so hard that it temporarily knocked him unconscious. He was carried from the track where it was found that he had not only hit his head but he had also hurt his arm and lacerated his leg. His injuries were treated by a German doctor but by the following day his leg had become infected.

As the fifth and final day started Wilkinson’s leg had gotten much worse and his knee was swollen and tightly bandaged. It was still being treated and dressed every hour or so until eventually the doctor advised that he should return to England by air immediately for treatment. Wilkinson flatly refused. Wilkinson had qualified for the finals of both the 1000 metres and 1500 metres and knew that by not racing these events they would automatically be forfeited. He was most vocal about ‘giving the crowd the spectacle they deserved’ especially as he had struck up a rapport with many of them. Having given his advice, the doctor refused to take any further responsibility should Wilkinson’s condition worsen and so Wilkinson stepped back onto the track for the 1000 metres final against Mathis. Mathis got the better of the British skater, but only just, and despite his injury Wilkinson took home yet another silver medal and in doing so gave much credit to his French opponent. With one last event to go, the 1500 metres, Wilkinson again stepped onto the track and despite all the odds Wilkinson sprinted to the front with three laps remaining and held on to the finish. Despite his obvious discomfort, through shear grit and determination he was now a double European Champion.

After the competition concluded Fred Renkowitz, the FIPR President, heaped much praise on Wilkinson for his sportsmanship and pluck in racing when it was quite clear he should have been in hospital. On his return to England, Wilkinson was rushed to hospital where he remained for a period to aid his recovery. Unfortunately, this meant that he was not able to defend his Half Mile British title held just a few days after the team returned. Unbeknown to Wilkinson at that time he would never win another British title, but greater things were still to come.

A few months later after his recovery Wilkinson’s interest in roller derby was piqued. How that came about is not clear but in the autumn of 1936 he was taking part, albeit not seriously, in some roller derby training sessions at the Brixton rink along with Benny Lee, former roller skating legend and now Streatham ice rink manager. Wilkinson’s interest in roller skating had always been shared between speed and hockey and by November he was appointed as captain of the All Blacks roller hockey team. With roller derby now added to his repertoire of skating activities Wilkinson spent more time on his skates than off them.

Around this time a six day race at Harringay Arena was announced. It was a revival of a race that had taken place many years before and Lee approached Wilkinson to pair with him for the event. The problem was that to do so would mean that Wilkinson would have to give up his amateur status, something Lee had done back in 1926. Whilst Wilkinson pondered this, he continued to train with Lee at the Brixton rink six days per week, Saturday’s being his only day off.

On December 12th (1936/37 season) and with a record number of entries (41) the Half Mile Championship was held at Granby Halls, Leicester. Due to his injury sustained in Germany Wilkinson had been unable to defend his title back in April, but now he was hoping to make amends. He qualified for the final, as did Reed, Ross and Pete Walters (Herne Bay). Before the final Wilkinson, Reed and Ross were introduced to the crowd to much applause as their exploits in Stuttgart were warmly recognised. Eventually the draw for starting positions was made and Wilkinson drew the outside. There had been much talk about the starting arrangements at Granby Halls suggesting that those on the outside were at a significant disadvantage, especially for the shorter distances, and so it proved. Reed, who had drawn the inside, would finish first and Wilkinson could only manage third place. It would be his last individual British championship medal. The One Mile Championship was held on 14th January 1937, at Alexandra Palace where the semi-finals and finals had a B.B.C. sound recording of the running commentaries made by Marsh and Lord of the NSA and was broadcast later in the week. It was the first time a broadcast had been made of a roller speed event by any broadcaster worldwide. Sadly, another fall in training leading up to the event resulted in a pulled leg muscle which meant that Wilkinson would again be absent from the start line.

On 4th February 1937 Broadway attempted to retain their British relay title, again the race commentary recorded and later broadcast by the B.B.C. Despite the team consisting of Wilkinson and new sixteen year old wonder kid, Jackie Robbins, Broadway were beaten by Alexandra Palace. A few fumbled changeovers did not help and as Wilkinson skated the final two laps ferociously he could not close the gap on Reed who finished one second ahead of him. Wilkinson’s relay medal was to be the last domestic medal he would achieve in his skating career. Not feeling a hundred per cent and still with his troublesome knee from Stuttgart, Wilkinson took to the Forest Gate rink on 24th February with the aim of winning the Five Mile Championship for an unprecedented fourth consecutive time, but this too was not to be. He would come home in fifth place which, for some of those who knew his condition, felt that this was still impressive. For Wilkinson it wasn’t the performance he was hoping for and the question about whether he would join Lee and Reed in becoming a professional skater was finally answered. Wilkinson decided that he would retain his amateur status and looked to the 1938 season for his resurgence amongst the domestic ranks. With training somewhat restricted on the Cricklewood rink, the venue now also being used to host wrestling matches on a Sunday, Wilkinson left the Broadway club and briefly rejoined the All Blacks.

His first venture of the new season, however, also resulted in disappointment. The Half Mile Championship was held on the extremely slippery Boulevard rink, Leicester, on 4th December 1937 (1937/38 season). Wilkinson qualified for the semi-finals but was beaten by two yards by local skater Ken Blakesley (Boulevard) on his home track. It was a shock upset to say the least but Blakesley would go on to take the bronze medal in the final. Wilkinson did not make an appearance for the Five Mile Championship at Alexandra Palace on 10th January 1938 and there was to be further disappointment in the Mile Championship at the same rink on 20th January. In his heat Wilkinson and a heap of other skaters fell heavily resulting in yet another significant gash to his leg, this time down to the shin bone. The race was immediately stopped and re-run, but whilst Wilkinson won his heat he would fail once again to progress through to the final. Despite his efforts and aspirations luck was definitely giving Wilkinson a wide berth.

Also, in January 1938 and having now joined the FIPR it was announced that Great Britain would host the very first World Track Championships (initially promoted as a European Championships) at the Wembley Sports Arena in April. The Empire Pool, as the building was also known, was presently a makeshift ice rink but with a feat of engineering ingenuity a sprung wooden floor would be installed to convert it to a hard floor suitable for roller skating. In June 1937 the FIPR had held the very first World Championships on the road in Monza, Italy, but as with the European Championships of 1930 and 1935 the NSA were not affiliated to the FIPR and did not recognise road races as legitimate competition. These two factors again resulted in Great Britain being unrepresented at these championships.

Now, though, Wilkinson set his sights on being named in the 1938 British team but this time it would not be the foregone conclusion as it was back in 1936. It had already been announced that the team would be selected after the conclusion of the British Championships and the running of a series of trials. Wilkinson had not placed in any of the championship events and by his own admission he was out of form. Despite Jimmy Reed no longer eligible due to his professional status, there were a whole host of other wannabees eager to get in on the action. These included the likes of teammate Jackie Robbins, the newly crowned Half Mile Champion Doug ‘Don’ Jackson (Leicester), Eddie Stumbke (Alexandra Palace), Frank Lamb (Broadway), Pete Walters (Herne Bay) and of course Wilkinson’s former British teammate, Bill Ross (Alexandra Palace). Undaunted by the adversity he faced, Wilkinson set about the task of trying to convince the selectors he was once again worthy of a place on the team. Before that, however, was the small matter of the British Relay Championships.

On March 10th on the Alexandra Palace rink Wilkinson surprisingly turned out for the Forest Gate team. The reasons behind this are unknown, but in the qualifying heats Forest Gate drew Medway. Medway, however, failed to field a team due to illness and Forest Gate received a bye into the semi-finals. Here they drew holders and odds on favourites, Alexandra Palace. What ensued was not only one of the most spectacular relay races witnessed in a generation but also the setting of a new track record.

Unfortunately, as predicted the record and victory would go to Alexandra Palace but it was not as one sided as all had expected. Despite a close and hard fought contest, a muddled changeover between Wilkinson and Savage resulted in Ross getting the upper hand for Palace and they held on to the finish, crossing the line just a half yard ahead of Forest Gate.

Just over a week after the relay the trials for team selection started in earnest on Monday 21st March on the Alexandra Palace rink. First up was a twelve mile race (189 laps of the rink) in which Wilkinson came home first ahead of Arthur Cooper and Frank Lamb, both Broadway. Wilkinson wasn’t counting his chickens but on the face of it he was starting to once again find form just at the right time. Over the next few days he continued to impress and when the trials were concluded Wilkinson’s name once again appeared on the British team sheet. Ross also made the grade once again but in place of the now professional Reed the young Arthur Cooper (Broadway) was named as the third skater.

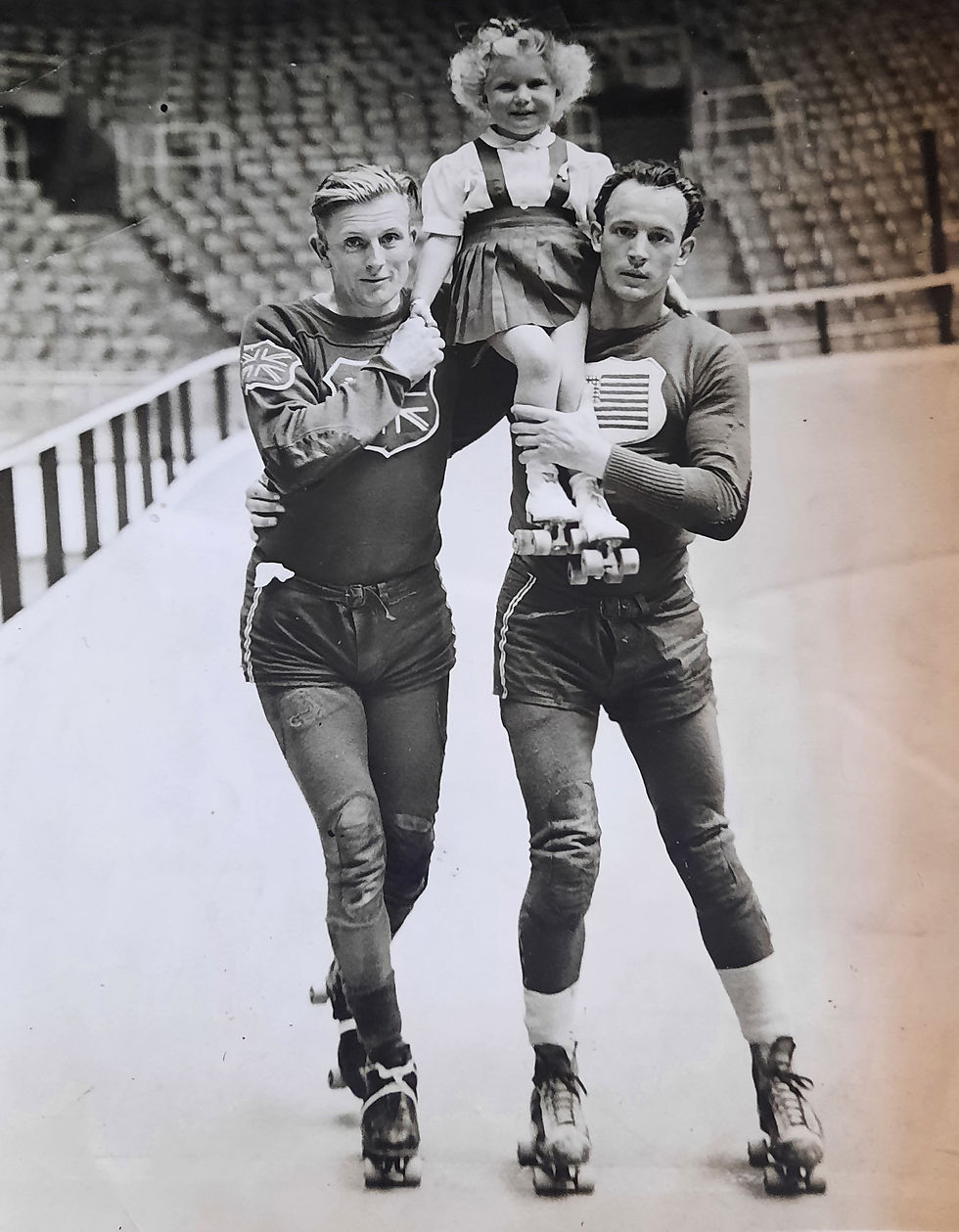

The international events would be held over three days at Wembley starting on Easter Monday, April 18th. With a crowd of some three thousand spectators and a track measuring 120 metres the championships started in earnest with the 5000 metres (41 laps) mass start event. Throughout the race the positions chopped and changed but with two laps to go Ross hit the front closely followed by Wilkinson. Ross finished first to claim Britain’s first ever World Championship gold medal with Wilkinson a half yard behind him to take the silver. The second event was the 500 metres. This sprint event was basically a knockout competition raced off in pairs. Wilkinson progressed through to the final where he would meet Arturo Garagnani (Italy) but unlike the earlier round the final was taken as the best of three. Garagnani was already a double European medallist from 1935 in Monza so Wilkinson knew he had his work cut out. Wilkinson, however, would beat the Italian in the first two run offs and secured so his place in history as the first British skater to be crowned British, European and now World Champion. (Incidentally, only one other British skater has achieved this feat – John Folley when he won a European title in 1971 having already been crowned World Champion in 1969).

Day two started pretty much as day one concluded. The first event was the 10000 metres and again Ross skated to victory, Wilkinson second and Cooper third, making it a clean sweep for Great Britain. The following event, the 1000 metres, did not go quite to plan. In the quarter finals Wilkinson again faced Garagnani in a head to head. He again beat the Italian only to then find out he had been disqualified for impeding. In fairness to the Continental officials, they asked that the disqualification be removed, but in typical ‘pompous fashion’ the British officials refused and the disqualification of Wilkinson stood. Even more controversy ensued when initially Cooper was awarded third, but after much discussion the officials decided that Cooper and Wilkinson should race off for third place the following day.

The third and final day started with the 20000 metres. The race was full of thrills and spills, thankfully this time none of them involving the British contingent. The Belgians set a hot pace from the start but their regular attempts at breaking away were constantly reeled in by Ross and Wilkinson. The attrition took its toll on a number of skaters and then with three laps to go Gaston Bogaerts (Belgium) and Italo Beretta (Italy) collided and fell, the latter being removed from the track unconscious. Wilkinson took the lead but rounding the final bend on the last lap he slowed and a fast finishing Arthur Cooper passed him to win his first title. So close behind was Albert Taeymans (Belgium) that he too overtook Wilkinson to claim second place. Whether Wilkinson slowed deliberately we shall never really know, but those who knew him believed he did so knowing that both he and Ross had got world titles but Cooper was still to achieve that feat. With Cooper being so close behind it allowed Wilkinson to slow up enough to ensure his teammate could realise his own dream. There may also have been an element of guilt in Wilkinson, knowing that he would shortly be racing Cooper for a medal in the 1000 metres, despite Cooper having been initially told that the bronze was his. Whatever the reasons, that unselfish act ensured that each member of the British team would now be recognised as World Champions. It was the first time a national team had all its members win World titles at a single event. That feat would not be repeated until Italy did it in 1953.

The evening session started with the 1000 metres run off between Cooper and Wilkinson and it was Wilkinson who would take the bronze medal. The final event was the 1500 metres with all rounds including the final again run in pairs. Being almost a mile, it really became a cat and mouse and long drawn out affair. Wilkinson drew Alberto Vento (Italy) in his heat and the skaters almost came to a dead stop whilst they tried to outwit each other. To much amusement a picture of a snail appeared on the telewriter (big screen for the watching public) at which point Wilkinson put in a burst of speed and he finished five yards clear of his opponent. Wilkinson reached the best of three final against the Belgian, Gaston Bogaerts and again employed these ‘slow’ tactics. With one win each the final came down to a decider and it was Bogaerts who would take the victory by mere inches from Wilkinson. There was much discussion and criticism about the slow tactics employed in the 1500 metres, not only by Wilkinson but also the other two British skaters. It was generally believed that the British skaters were well equipped and strong enough to have made the races hard and fast and that the overall performances in the 1500 metres could have been much better. What few could accept was that not only had the three British skaters competed in all events, including a gruelling 20000 metres where many skaters from the other nations failed to finish, but what was effectively a 1500 metres knockout with several qualifying rounds was nothing short of ludicrous. Regardless, Wilkinson had achieved a full set of medals, gold, silver and bronze in what were classed as the sprint events – the 500 metres, 1000 metres and 1500 metres. This resulted in Wilkinson being crowned the Overall World Sprint Champion and was awarded a special jersey in recognition of this. Incidentally, Ross would be crowned Overall World Distance Champion for his results in the 5000 metres, 10000 metres and 20000 metres.

For Wilkinson his speed skating achievements since he first strapped on a pair of skates some fifteen years earlier had now reached a pinnacle. There was nothing he hadn’t won. He continued to enter the odd race, one of his last being the Burditt Cup at Leicester on 1st December 1938. The race itself saw the largest number of entries for any race since 1910 and it was also notable for the very first use of the ‘black flag’, issued to Arthur Storie (Forest Gate) who received a month’s suspension. On 16th March 1939 he was due to race in the British Relay Championships for Forest Gate but that morning his father passed away and understandably Wilkinson gave his place up on the team. It was obvious that he was now tired of racing and decided to take a break from speed skating. He returned to playing rink hockey with a resurgent All Blacks team who had made the recently opened Walthamstow Sports Centre their new home, all the while contemplating what should come next.

In early 1939 he was now living in Brixton, a mere stone’s throw from the rink in Water Lane. That coupled with the death of his father probably made him think that life was too short and so in June he finally made the decision to turn professional. By doing so not only opened up new challenges for him with regards to racing the likes of Benny Lee and Jimmy Reed, but he would also get paid for it. In addition, roller speedway (derby) was taking off at a rate of knots that saw the Harringay Arena packed out night after night. Wilkinson eventually joined Reed as one of the European team members that would take on the Americans in what would become a huge draw and a fantastic spectacle for the watching public. Such was the popularity of the sport (if you could call it that) that European skaters were invited to race in America, again for money. Who could resist travelling and getting paid to do something you loved? As the skaters packed their suitcases suddenly the world came to a crashing halt. On 3rd September 1939 Great Britain declared war on Germany.

The effect was almost immediate. Within a few months most of the roller rinks had closed their doors as many of their patrons joined the forces and did their bit for King and Country. Wilkinson joined the RAF as ground crew and was stationed in Egypt, doing his bit in the efforts to defeat Hitler. When the war was eventually won in 1945 Wilkinson was 38 years old and any thoughts of roller speedway were now furthest from his mind.

With professional skating opportunities virtually non-existent in 1949 Wilkinson approached the NSA and requested if they would consider reinstating his amateur status. His application was reviewed and approved and he quickly dusted down his roller skates and took up his position once again as a member of the All Blacks (now known as the Broadway All Blacks) roller hockey team.

In 1952 his wife, Winifred, died but in early 1954 he would find love again and marry once more with his second wife, Irene, bearing him a son later that year. Wilkinson’s love of roller skating meant that he would continue to be a member of the Broadway All Blacks and would occasionally don his skates to take part in the occasional hockey match but on 16th February 1963, after a long illness, Harold Wilkinson would pass away aged just 55.

Writing about Harold Wilkinson's exploits here does not do him justice. It is difficult to comprehend his invincibility in speed skating circles in the mid 1930’s. To be one of only two British skaters to have ever won individual British, European and World Championships is an accolade that few will be aware of and even fewer will ever achieve. He was a true British skating legend in every sense, whether that be his ability, his courage and determination or simply his sportsmanship. The editor of Roller Skating Magazine, the late great Cyril Beastall, wrote an obituary to Wilkinson in the April 1963 edition of his publication – it was titled “Passing of an All-Time Great” and he summed him up perfectly…

“A great enthusiast all his skating life, and a true sportsman, Harold Wilkinson will long be remembered for himself as well as for the great deeds on the racing track”.

#12 in the list of senior British men to have represented Great Britain (1936-1938)